|

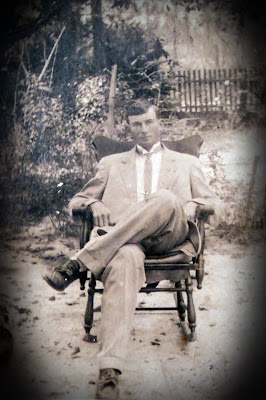

| Dr. Willis S. Smith home - Rawl's Hill Plantation, Clark County, Arkansas |

Transcription (copies of article below):

By Farrar Newberry

Even though he wore a flowing white beard, his hair remained dark down to old age, so that friends accused him of dyeing it. About six feet tall, dignified and imposing, his friendly manner was well calculated to attract attention and to make friends. A son wrote of him in 1930 that "he carried a great amount of energy and perseverance."

The great-grandfather George Smith, came over from Ireland some time in the 17th century and settled in North Carolina in time for his own son Willis to enlist in the Revolutionary army and meet his death at Bunker Hill. Willis' son, Millington, went west after the war and spent some time in Tennessee before going to Todd County, Kentucky, where our subject was born on Aug. 10, 1810. However, the family shortly settled in Johnson County, Illinois, where the lad grew to manhood.

Though deprived of early schooling, Willis Smith's driving ambition prompted him at the age of 20, "unable," as he later said, "to write my own name and to read and spell but little," to seek an education. Accordingly, with three neighbor boys, he went by ox-cart the 100 or more miles to Rock Springs, and with the aid of Principal John Mason Peck, entered the Theological Seminary there. The boys built a crude log cabin and "batched" doing any sort of odd job that could be found, to pay their way.

Willis, in a year or so, taught an elementary school during vacation, and the pay, though small, helped with his tuition at the seminary and later at Shurtliff College at Alton, where he finished the college work and was graduated.

There had developed so close a friendship with Dr. Peck that Smith would in a few years name a son for him, and would write, late in life, that the "tie has never been broken or forgotten."

In the summer school he had taught he learned from a pupil who came from Clark County, Ark., of the opportunities available in that state, and "pulling up stakes," he left immediately. Stopping en route in Cape Girardeau County, Mo., he lingered long enough to teach two terms of school. Then, accompanied by an older brother, he journeyed horseback to a place near the present Okolona, where he taught a three months term before leaving for nearby Rome at that time a thriving little village, now a ghost town, to teach for a whole year.

Young Smith must have had a winning way about him for two years after--1835--he offered for and was elected sheriff of the county at the age of 26. In that capacity he was to serve the people for eight years and until voluntary retirement. For seven of those years the county seat was at Greenville, near the present Hollywood. His last year in office was at Arkadelphia, to which the seat was removed in 1842.

It was nearly half a century later that Willis Smith wrote reminiscent articles for the Southern Standard and Gurdon Advocate. Some of the articles give thrilling accounts of court proceedings during his incumbancy as sheriff.

One of the cases described that of John H. Mosely, indicted as accessory before the fact of stealing horses from Indians who were being sent south along the old military road. Horse stealing in that day was a capital offense, and Mosely's prominence made the trial a matter of county-wide interest. Such outstanding lawyers as Albert Pike and Grandison Royston took part and a verdict of guilty was returned and sentence of death pronounced. The date for the hanging was set for 20 days later, and sheriff Smith had to employ a dozen deputies to guard the insecure jailhouse. The day for execution came, the prisoner was shrouded, and seated upon his coffin, was started for the gallows. At the very last minute one of his lawyers galloped up with a reprieve from Governor Conway. A little later came a full pardon, whereupon Mosely said to a crowd of his friends who had gathered, "Come up to the grocery, boys, and have a drink!"

Another case involved the then legal penalty of laying on the lash. There were two defendants, both found guilty. One was sentenced to stand in the pillory two hours, "take 79 lashed on his bare back," and remain in jail for another 24 hours. The other was to get only 50 lashes. Smith wrote that he gave one ten strokes of the whip and let him rest while he gave the same number to the other, and so until he had finished the unpleasant job. "There," he wrote, "I made the only men drunk that I can recollect." This was, of course, to deaden the pain of the victims.

The idea of temperance had been instilled into Willis Smith when a student of Dr. Peck, and for the rest of his life he fought the liquor traffic at every turn. He hated the places where the stuff was sold, called them "dead-falls," and often uttered the prayer, "God, keep us sure in our determination to bar it from the whole county."

At some time during his years as sheriff, Smith took up the study of medicine under a younger brother who was a graduate of Louisville Medical College. It was more than a decade later that he himself was able to complete the course at a medical school in Memphis, and began active practice. In the meantime he purchased the Rawls Hill Plantation some two miles south of Whelen Springs on the Camden road. This he eventually built to an estate of over 1200 acres; and though his active career as a doctor practically ended with his retirement in 1876, he continued to farm for the rest of his life.

Loving the country and disliking towns and cities as places to live he remained on the plantation, with the exception of two years, until his death in 1891. Those two years were spent at Mt. Ida, where he waited on the sick while serving Montgomery County as Judge by appointment of the governor.

Only persons now in middle life, or near it, can recall the old-time country doctor, who carried his medicines in his "pill-bag," looked after the ill and afflicted without benefit of trained nurses, and often stayed at a bedside all night to save a patient's life.

Dr. Smith's account book covering the years 1851-60 listed many visits over a wide range of country, with fees charged and prices of medicines and treatment. Pills for "ague," appearing frequently in the book, cost $1.00; "bleeding" was $1.50; four portions of quinine totaled 58 cents; castor oil was 25 cents; a bottle of bitters was listed at 50 cents, and syrup of squills came to $1.00. (Squills came from the fried roots of lillies and was used as an expectorant.) The highest fee appearing in the book was $5.00 for obstetrics. Pretty cheap for a brand new baby!

Willis Smith's family life was happy through two marriages; the first to Miss Margaret Janes and the second to Mrs. Martha Harris. To the first union came 8, and to the second 7 children.

His character exemplified high morals and sound religious beliefs. He was a Council Mason, and from the age of 20 an ardent member of the Baptist church. His memoirs relate that he "taught, or tried to teach," the first Sunday School class in Clark County. This occurred in 1833 soon after his arrival for teaching the country school, and it is said this inter-denominational group of students ranged in ages from 5 to 65.

Though he cast his first vote for Andrew Jackson, he called himself a constitutional old-line Whig, and when the Republican party offered its first candidate for President in 1858, he "joined up" for keeps. He opposed on principle of secession, but staunchly supported his adopted state after it joined the Confederacy.

Willis Smith's great interest was in people, and especially those of his own community, who he tirelessly served as physician and neighbor for so many years. And when he died at 81 and was laid to rest in the family plot near the plantation house, the local correspondent of the Arkansas Gazette paid this tribute: "Our town mourns the death of Dr. Smith. He was an industrious and energetic citizen, always ready to do anything for the prosperity of his community."

nu=3236)6+6)+;)23276+6;9(7+5ot1lsi.jpg)